How do you write epistolary fiction?

“So I want to write a story that’s told through letters and texts and stuff? Like, I’ve seen books that are all emails or diary entries and I think it’s really cool, but I have no idea how to actually do it.”

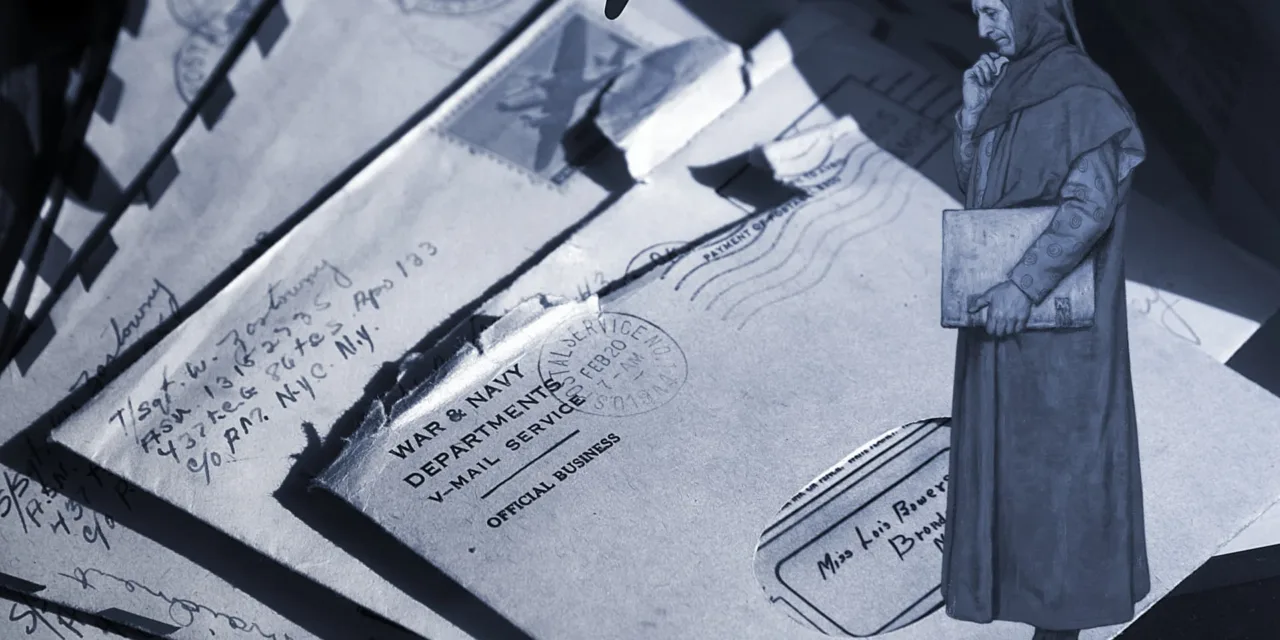

There’s something irresistibly intimate about stories told in an epistolary style. Whether it’s a love note slipped between diary pages or a transcript of an interview from decades ago, it puts readers directly inside a character’s head without any narrative filter. It’s raw, immediate, and deeply personal.

The form has been around for a really long time, but in recent years has had a massive surge in popularity. In fact, the digital age has given writers more document types to play with than ever before.

What exactly is epistolary fiction?

Epistolary fiction is simply a story told through documents. The term comes from the Latin epistola, meaning ‘letter,’ but modern epistolary fiction has expanded far beyond that.

A lot of epistolary fiction unfolds through:

- Letters and postcards.

- Diary or journal entries.

- Emails and instant messages.

- Text conversations.

- Social media posts, comments, or DMs.

- Newspaper clippings and articles.

- Official documents, reports, or transcripts.

- Audio transcripts.

- Any combination of the above.

Classic examples of epistolary fiction include Dracula by Bram Stoker, which weaves together diary entries, letters, and newspaper clippings. And more recently, Janice Hallett has become one of my favourite epistolary writers. All her books (like The Appeal and The Twyford Code) have a central mystery that is slowly revealed through a combination of text messages, emails, and transcripts.

Why choose epistolary fiction?

Epistolary fiction offers storytelling advantages that traditional prose can’t replicate. Readers experience events as they happen, filtered through a completely biased voice and perspective. There’s no omniscient narrator telling you what’s happening. You get only the facts, the subjective perspective, and so the construction of the book itself does the heavy lifting in terms of subtext and understanding.

I personally think that epistolary fiction is one of the more interesting formats, but also one of the hardest to get right. It’s easy for it to become just a series of boring info-dumps, so it’s important to know what it does well, to know whether it’s right for your story.

Instant intimacy

When characters write letters or diary entries, readers experience their thoughts in real time. When you have a transcript of an interview, you hear their voice. There’s no narrative distance smoothing out emotions. You’re right there with them, feeling their confusion, hope, and fear as it happens.

Built-in unreliability

Every document is filtered through a character’s perspective, which means every document is inherently biased. Characters lie, omit details, misremember, and spin narratives. When readers piece together the truth from multiple flawed accounts, they become active participants in the story. There’s also an extra layer if you use a framing device that compiles these documents with a purpose.

You get to say a lot with what you choose to omit

What isn’t said can be as powerful as what is. What’s not included in your epistolary documents (the missing responses, the things characters choose not to write, etc.), create organic tension. Readers notice gaps and silences, filling them with their own suspicions and interpretations. This makes the reading experience far more engaging as it’s easy to let your imagination create red herrings that feed into narrative twists.

Unique voices

Because each document is from the point of view of one or multiple characters, you’re forced to develop unique voices from the start. Each character’s vocabulary, sentence structure, and tone must be distinct enough that readers can identify who’s speaking or writing without being told more than once.

Choosing your document types

It goes without saying that the format you choose should serve your story’s era, characters, and tone.

- Traditional letters work beautifully for historical fiction or when physical distance separates characters. They allow for longer, reflective passages and can convey anything from stiff formality to deep intimacy.

- Diary entries offer direct access to a character’s inner thoughts without addressing another person. They’re particularly effective for coming-of-age stories where the protagonist has no one to confide in, or at points in the story where something personal or intimate needs to be revealed.

- Digital communication suits contemporary settings. Emails range from professional to personal, while texts capture rapid-fire, abbreviated conversations and are great for unique character voices through their texting style.

- News stories and articles provide external perspectives and world-building context, revealing how events appear to those outside your main characters’ immediate circle.

- Official documents like police reports, medical records, or court transcripts add authority and can reveal information characters might hide in personal communications.

- A mixed-media approach is when you combine multiple document types in a single story. It allows you to present events from various angles and vary your storytelling rhythm. Some of the most inventive epistolary novels do exactly this.

Structuring your epistolary story

One challenge of epistolary fiction is pacing when your narrative is fragmented across different documents. So how do you tie everything together and stop things feeling stale and boring?

Give readers a frame

A framing device helps readers quickly understand why these documents exist, and why they’re reading them. Are these letters discovered in an attic? Is this a dossier compiled by investigators? Is someone reading through their late mother’s emails? A clear frame helps readers settle into the unusual format or can help change the way a reader experiences it. For example, if we look at Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale it isn’t clear that the novel is epistolary until we get to the framing device, which re-contextualises the entire novel.

Make every document earn its place

Each letter, email, or diary entry should serve a purpose. What changes because of this document? What does the reader learn? What question does it raise? All documents should advance the story either directly, by setting up a future reveal, or as a red herring.

Vary your pacing

Epistolary fiction can drag if documents become too long or reflective. Mix up your document lengths and types, or commit to a single type with a narrative frame. The second will replicate a more traditional prose approach, so your narrative frame will have to do a lot of the heavy lifting.

Handle time carefully

Dates, timestamps, and clear markers help readers track when events occur, especially when documents arrive out of order or multiple storylines interweave. That said, you can create deliberate ambiguity around timing to create mystery or to be tactful around when you reveal something, but it still needs to be clear to a reader when in the story the document positions them.

Making each voice authentic

Voice is one of the most essential elements to get right in epistolary fiction. Not only does each character need a distinct voice, but the style also needs to be believable for the type of document that is being recreated. A character who is a journalist will have a different style in their professional writing than they do when they text with their best friend, but in those message exchanges, both the journalist and their friends must be uniquely distinguishable.

Remember that people perform on the page. Even in private documents, we curate ourselves. A diary-keeper might romanticise their suffering. A letter-writer might project more confidence than they feel. It’s absolutely essential in epistolary fiction to know your characters inside out.

Things to watch out for

- The info-dump: Beware of characters conveniently explaining things the recipient would already know. “As you’re aware, dear sister, our father made his fortune in textiles…” Real correspondence doesn’t work this way, so you’ll need to think outside the box to reveal this information.

- Too much reflection, not enough action: Direct access to thoughts can tempt endless introspection. Things need to happen, and readers need to see or hear about those events.

- Knowledge tracking errors: With multiple perspectives, it’s easy to accidentally have a character reference information they couldn’t possibly know. Keep careful track of who knows what and when.

- Format limitations: Characters can only write about what they’ve experienced or been told. If something crucial happens, you need a plausible way for at least one document to share this information with the reader.

Read a lot, then read some more

I can’t emphasise enough how vital it is to read a lot of epistolary fiction if it’s a path you want to go down. How experienced authors handle the challenges of the style can teach you so much, and there are some absolutely amazing examples out there.

My personal recommendations are any of Janice Hallet’s books, Possession by A. S. Byatt (it’s a hybrid book that combines traditional prose with a dual timeline epistolary PoV), and the Themis Files trilogy by Sylvain Neuvel. But I’ve put together a book list of other great epistolary novels below.

Note: All purchase links in this post are affiliate links through BookShop.org, and Novlr may earn a small commission – every purchase supports independent bookstores.